The PS4’s latest blockbuster moviegame Detroit: Become Human is like something my Alexa would come up with, were I to ask her to write a story about androids with feelings.

As I imagine it, the vaguely sinister, sporadically helpful digital assistant that currently resides on my desk would quickly synthesize a bunch of pop sci-fi touchstones—a dash of Battlestar Galactica, a pinch of Westworld, a touch of A.I. Artificial Intelligence—and mush them together into a robo-generated trope casserole much like the one currently cooling on my PS4’s hard drive. Her script would have all the hits: The scene where the robot risks its life to save a human, the scene where the guy who hates robots finally comes around, and at least two scenes where a robot looks at itself in the mirror and ponders its identity. All the hits and nary a fresh idea among them.

In Detroit, it’s the year 2038. Thanks to technological advances and a shift in manufacturing demand, the Motor City has become the Android City. The rest of the world is pretty much like it is now, only worse. Climate change? Still a problem. Overpopulation? Ditto. An escalating diplomatic crisis between the the U.S. and Russia? Yup. In fact, most of this game could be taking place five years in the future, not two decades. The only thing about the Detroit of Detroit that feels appropriately futuristic is the fact that, for around eight grand, you can buy a lifelike android to help out around the house.

The story, which I completed in around 10 hours on my first playthrough, focuses on three of those androids: a domestic servant model named Kara, who attends to a young girl and her abusive father; another servant named Markus who cares for a kind, elderly painter; and a prototype law enforcement model named Connor, who is investigating a rash of android “deviants” who have been violently turning on their masters. The player’s perspective hops among the three as Kara goes on the run, Markus begins organizing an android uprising, and Connor attempts to get to the bottom of why so many of his kind are rebelling. Each narrative thread unspools on its own for the first few hours, as players make decisions that redirect the story and snip off alternate outcomes. Spare a character’s life, and he may turn up to help out at some point down the road. Make an enemy, and you’ll have to reckon with her later.

This review is based primarily on my first playthrough, which I view for the most part as canon. It is possible for the main characters to die at various points in the story, even unusually early on, but I was able to shepherd all three of them to the final credits intact, leading to what I’d call the “good” ending.

I’ve since experimented with story branches I didn’t see, though there are still some things I haven’t experienced. Most of those alternate branches felt like exactly that: alternatives to a primary option. With the exception of some major last-act decisions that I could see going differently, my first playthrough seems like the one most players will likely see, unless they go in with the goal of testing the game and making purposefully out-of-character decisions. Regardless, I should acknowledge that I haven’t played through every permutation of every scene in the game. Given how unexcited I feel about the prospect of spending another couple hours unlocking additional paths, I probably never will. At least there’s YouTube.

Apart from a couple of climactic convergence points, each sequence in Detroit plays like a standalone vignette. You’re put in control of one of the characters as he or she attempts to navigate a difficult situation, each of which takes around 20 minutes to play out. Kara tidies up the house and attempts not to ruffle her violent owner’s feathers. Markus helps his wheelchair-bound master return to his home studio before navigating a conflict with his human son. Connor visits his new, android-hating partner at the police station and attempts to break the ice. Especially in the early goings, these sequences feel as much like free standing proofs-of-concept as they do chapters in an ongoing narrative.

A science fiction story is only as interesting as the society it imagines, but Detroit’s theoretical future is unfortunately dull. In this vision of 2038, people still use personal computers and play MMOs, magazines still reside on touchscreen tablets, and cars are basically just futured-up versions of the self-driving prototypes we see on the tech blogs of today. The sole fantastical element is the fact that there are advanced androids everywhere, a transformative technology that serves to make the rest of the world feel all the flatter. Detroit is so eager to get to the hot robot morality action that it largely neglects to fill in the small, surprising details that make sci-fi futures so fun to ponder.

Two decades is a long time. Twenty years ago, Donald Trump was just a real estate jerkoff from Queens, Beyoncé was just a member of an up-and-coming girl group, and 9/11 was just a phone number. Many Americans didn’t even have an email address, let alone broadband internet access. By the time 2038 rolls around, the world will likely have changed in ways most of us couldn’t possibly imagine. It is, in part, the charge of science fiction authors to do that imagining on our behalf, offering us glimpses of our possible futures and, perhaps, helping us better understand our present. Detroit simply takes the most pressing concerns of 2018, advances them a few unimaginative steps, and calls it a day.

As in developer Quantic Dream’s previous games, Detroit is on its surest footing when it pulls back from the big questions and focuses on the mundane. In their 2010 mystery game Heavy Rain, you might spend some time cleaning up after your kids, or rock a baby to sleep. In 2013's Beyond: Two Souls, you might attend another grade schooler’s birthday party, or hurriedly clean up your apartment before a first date. (Since I know people will ask about this if I don’t mention it: I haven’t played the studio’s first two games, Omikron and Fahrenheit.) In Detroit, Kara and Markus are both servant models, and early in the game both are content to follow their domestic directives. They do as they’re told, helping their humans and picking up after them, preparing food and running errands.

I found these quiet sequences oddly engrossing, at least for as long as they lasted. As Kara or Markus, I could just relax and do a repetitive job, with no complex decision-making required. Doubtless some of my enjoyment also came from the knowledge that any peace this game offered would be fleeting. Soon enough, the character I was controlling would be thrown into another fight for survival.

In Detroit, subtlety is invariably a prelude to histrionics. Nearly every sequence in the game, however quietly it begins, must end with absurd melodrama or a high-stakes showdown. That might mean that your abusive owner has a sudden violent outburst, or it could mean a stranger enters the scene and immediately threatens you. The humans in Detroit behave like 90s cable TV characters, all shouting and monologuing, escalation and confrontation. “Here we go again,” I’d groan, as another conversation was interrupted by another menacing asshole. This is a world where cops settle procedural disagreements by immediately pulling guns on one another. It’s loud, stressful, and above all else desperate, as if the game is afraid that if players aren’t faced with a life-or-death situation every 10 minutes, they’ll get bored and go do something else.

Detroit was directed and primarily written by David Cage, a veteran developer who’s been outspoken about his desire to help games achieve some mythic cultural legitimacy currently reserved for more established art forms like film or literature. As in Cage’s previous two games Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls, Detroit takes a threefold approach to bridging that perceived gap: it emulates the visual language of film, places emphasis on emotive, motion-captured performances, and foregoes traditional video game control inputs in favor of contextual button prompts intended to more intuitively simulate the action on-screen.

In Detroit, turning a doorknob isn’t accomplished by pressing a button, it’s accomplished by rotating the right thumbstick in a semicircle. Turning the page on a touchscreen device requires sliding your finger down the PS4 controller’s touchpad. Dodging to the side sometimes requires moving a thumbstick, and sometimes requires physically swinging your controller to the side. Perversely, what began almost a decade ago in Heavy Rain as an experiment in alternative user experience design has been stripped down and calcified into its own peculiar set of arcane inputs, same as any other video game.

Far from being approachable and intuitive, I found Detroit’s control scheme to be impenetrable and frustratingly unpredictable. The jumbled user experience expresses itself most clearly any time the action ratchets up. At a moment’s notice, Detroit will demand that players quickly and accurately respond to flashing, varied button prompts in order to win a fight, chase down an adversary, or otherwise survive a dangerous situation.

Whenever an action sequence began, I sat upright in my chair and stared fixedly at the screen, bracing for another high-stakes game of Simon Says. My body would tense and my contact lenses would dry against my irises as I quickly reacted: Circle! Triangle! X! Right trigger! Left trigger! Square! Circle! Circle! I correctly responded to the vast majority of the action prompts in my first playthrough of Detroit, but each small mistake would leave me cursing and wondering if I’d just altered my narrative timeline.

Detroit functions in part as a tech showcase, and in that respect it does offer some undeniable appeal. It was introduced by Cage in everything but name at the 2012 Game Developers Conference, primarily as a way to show off the progress Quantic Dream had made with motion capture technology and their shift to full-body performance capture. Detroit is Quantic Dream’s first game designed for the PlayStation 4, and their technical artists have had a terrific time taking advantage of all that extra horsepower.

It’s all very shiny and fun to look at, and its visuals are bolstered by some evocative sound design, which at its most harrowing places you within the headspace of a malfunctioning or even dying robot. The results of Quantic Dream’s motion capture system are impressive as well, particularly any time the camera pulls out and one of the protagonists gets to pace dramatically around the room, gesturing and emoting before the peering eyes of dozens of performance-capture cameras. They still look like video game characters, but they look like video game characters with identifiably human actors underneath.

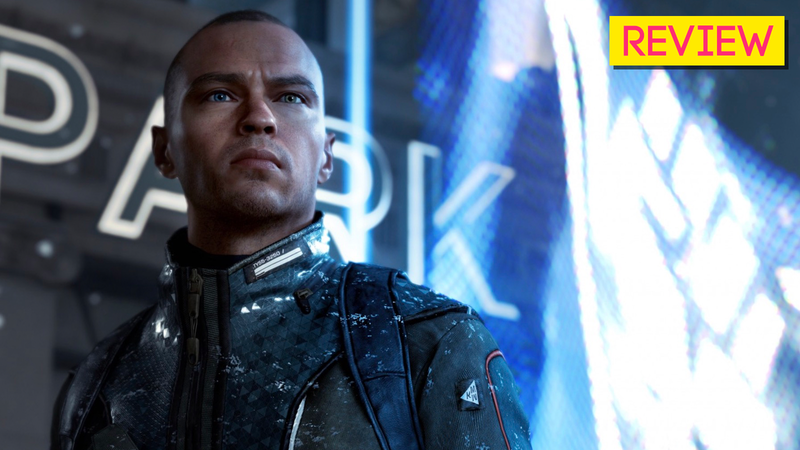

Lead actors Valorie Curry, Jesse Williams, and Bryan Dechart do well enough in their roles as the determined mom, the reluctant savior, and the dogged investigator, respectively. Veteran Hey-It’s-That-Guy Clancy Brown also deserves credit for his performance as Connor’s washed up drunk of a partner Hank, sprinkling on just enough exasperated charm to distinguish a shopworn cop-show archetype from the hundreds of other versions of the character already put to film.

With a solid cast, impressive performance capture technology, a stacked roster of technical talent, and an apparently bottomless budget, Detroit has so much going for it that it’s even more of a shame that it amounts to so little. The game is at its best when it stops trying to transcend its cheesy genre roots and instead embraces them. One highlight is a mid-game heist sequence that, in true Ocean’s Eleven style, is intercut with the planning session that preceded it. I knew that each action Markus undertook was part of a scheme he himself had dreamed up, but I had to execute it while he explained it, not after. It was a neat way to transfer a familiar film trope to an interactive format, and made me feel like the star of a glitzy caper flick. As a bonus, the following chapter had Connor investigating the crime Markus had just pulled off, slowly piecing together the culprit’s identity and motivations. If only this game were more frequently willing to drop the profundity and focus on the playful.

Unfortunately, Detroit has higher aspirations than groovy heists and cheesy drama. This game is serious business, it will have you know, as evidenced by the aggressively emotional soundtrack, melodramatic audio cues, and the fact that every character spends most of their time staring into the middle distance while looking constipated. At first it appears to have something to say about slavery, oppression, domestic abuse, and several of the other challenging topics passed on its cannonball run to the grand finale. Time and again, however, it simply depicts those things and moves on, as if checking off entries on a list of the “real world themes” Cage has said in the past that he wishes more games were willing to address.

In an early chapter, Kara attempts to clean her abusive owner’s filthy home as delicately as possible, all while he grows increasingly intoxicated in the background. It’s a well-executed sequence on its own, in that it accurately captures the dread of watching someone you live with drink and slowly lose control. You know this won’t end well, but you can’t say anything, because that would just set them off. So you walk on eggshells, praying that you can just finish your work and get clear before they drink too much or decide to engage with you.

Shortly afterward comes a violent, nightmarish confrontation in which Kara’s owner physically assaults both her and his daughter Alice. It can play out in a variety of different ways, and each one is awful. In one possible outcome, he beats Alice to death off camera, then kills Kara for good measure. Assuming you manage to avoid that outcome, Kara fights back, escapes with Alice, and… that’s pretty much that.

“I think people should see the scene, play the game and see it in context to really understand it,” Cage told Eurogamer’s Martin Robinson in a contentious interview regarding this sequence during a press junket last fall. “The rule I give myself is to never glorify violence, to never do anything gratuitous. It has to have a purpose, have a meaning, and create something that is hopefully meaningful for people.”

I’ve seen the sequence in context, and it still doesn’t work. It serves to introduce Kara and her bond with Alice, and sets Kara on her path toward deviancy and freedom. But after a brief discussion shortly after leaving the house, it is essentially forgotten. What meaningful thing did that scene say about domestic violence? That it’s bad? That living with an alcoholic is shitty and stressful? That watching a man abuse a little girl sucks? Okay. Like everything else in Detroit, the sequence is a one-off, leaving the dark complexities of domestic abuse and its aftermath mostly unexplored.

Underlying all of that is a bigger flaw in Detroit’s premise. The game is primarily concerned with artificial life as it pertains to humanity. It’s right there in the title: this is a game about Becoming Human. What is personhood? Can artificial beings achieve it? If so, should they? These are questions science fiction has been exploring for decades, yet in this case they have been answered before the first act concludes.

For starters, there’s the fact that while the three main characters are ostensibly androids, they are obviously “human” from the moment we set eyes on them, well before any of them embraces deviancy. They’re played by recognizable human actors. They emote just like the humans around them; in fact, they’re often more thoughtful and relatable than the melodramatic cretins with whom they so often interact. They laugh and scream, express confusion, frustration and sorrow, and appear to feel pain. When they cry, tears run down their cheeks. But far more importantly, they make human decisions because they are being controlled by humans.

When Connor was given the option to save a human life or focus on pursuing a suspect, I, a human, made that choice for him. Of course he saved the human. I’m a human, and I made a human choice. When Kara was given a choice to protect a screaming young girl or abandon her, of course I chose to protect the girl. Because of their agency as player-characters, Detroit’s androids are actually more human than the scripted human non-player-characters that surround them, which undermines the premise of Detroit’s central question. It could be a clever trick in a cleverer game, but here it just feels ill-considered, if it was considered at all.

Assuming that we in the real world continue to make advances in artificial intelligence at our current rate, answering the questions of if and when to grant rights to our creations will be immensely complex and challenging, if not impossible. Detroit skips the asking and jumps straight to the easiest answer—yes, obviously these people deserve rights—and is a less interesting game for it.

Partway through the story, Connor makes an earnest statement to his partner Hank. He follows up by joking that that wasn’t just his social management software talking—he meant it. Wait a minute, I thought, I want to know more about that! You have social management software? Do all androids have that? Is that what makes them act like people, or is it something else?

And while we’re at it, how do these androids function, on a basic level? What does their software actually look like? Is it somehow hard-coded to their physical body? They talk about dying, but can they actually die, or not? Do they feel real pain, or do they simply register damage? Why can they sometimes communicate with one another wirelessly, and sometimes not? Are they networked, and is any part of their personality stored in the cloud? Can they be hacked? Why do some androids look unique, and some look identical? Given that they can look like anyone, how do they determine their appearance? Speaking of that, where does their hair come from?

Detroit left me asking those questions and many more, and even a fairly patient plumbing of its unlockable character descriptions and alternate story branches has left me unsatisfied. Not only does it fail to flesh out its vision of the future, Detroit fails to even establish the premise of the debate it seems to want to encourage.

Part of my frustration with Detroit is that I’ve spent the last several years watching other game developers make far better narrative-focused games, often with substantially fewer resources. Dontnod’s unexpectedly ravishing Life is Strange looks like an old PS2 game compared with Detroit’s lavish production values, but it was consistently entertaining and even a little affecting. Telltale spent years routinely putting out licensed episodic adventure games that were excellent at best and serviceable at worst, despite having been churned out at an incredible rate in what sounds like a counterproductive, pressure-cooker environment. Just this year, Hazelight Studios turned the cinematic adventure format on its ear with the fantastic cooperative game A Way Out, and Supermassive’s 2015 PS4 exclusive Until Dawn proved that big-budget, performance-captured games can be brilliant fun, mostly by enthusiastically embracing the goofiest tropes of schlock horror.

And that’s not to mention other less obviously Hollywood-inspired narrative games like Soma,Kentucky Route Zero, Oxenfree, The Vanishing of Ethan Carter, Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, or What Remains of Edith Finch, each of which experimented with video game storytelling in entertaining and interesting ways. Heck, for all their flaws, even Quantic Dream’s own Heavy Rain and Beyond: Two Souls were more engaging and experimental than this. Detroit feels blunted and conservative by comparison, just a collection of pretty faces with little to say.

Occasionally as you explore a room in Detroit, you’ll come across a photograph. These photos are, strangely, often based on actual images of real people. It’s as if by showing you a recognizably human face, the game is willing you to connect its fictional world to the real one around you. They serve instead to emphasize its pervasive, empty artificiality.

Detroit tells a story of robots who look and act relatively human, making their way through a nonsense world where everyone, even the humans, doesn’t actually look or act human at all. It’s a fragmented radio broadcast from a valley within the uncanny valley, so many layers deep in unreality that it could never hope to make it out intact. Sorry, Siri; apologies, Alexa. You’re still just appliances to me.

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "Detroit: Become Human: The Kotaku Review"

Post a Comment